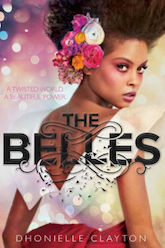

The Belles is Dhonielle Clayton’s debut solo novel. Published in the U.S. by Freeform Books (an imprint of Disney) and in the U.K. by Gollancz, it’s been attended by a certain amount of advance buzz and excitement: Clayton is an officer of nonprofit organisation We Need Diverse Books as well as a co-founder of small publishing house Cake Literary, and her first solo effort has many people deeply interested.

It’s always difficult for a much-hyped novel to live up to its advance praise. This doesn’t reflect on the book, but rather the expectations a reader brings to the experience of reading it. When it came to The Belles, my expectations were a little out of line with the kind of narrative that Clayton provided: this is a good book, but it feels very much like a debut novel. Its emotional beats lack the kind of complexity and nuance that I didn’t realise I was expecting until I failed to find them.

Buy the Book

The Belles

In the kingdom of Orléans, people are born red-eyed and grey-skinned—ugly. Belles—women with the power of beauty in their blood—can change the appearance of the citizens of Orléans, can make them “beautiful.” Belles are raised in seclusion, under strict control, and must live under tight rules. Every several years, the new generation of Belles competes for the position of the royal favourite: the victor dwells in the palace, while the others are assigned to teahouses in the capital or to the house in which Belles are raised.

Camellia is The Belles’s main character, and part of the new generation of Belles. There are five Belles in contention to be the new royal favourite—all of them raised as Camellia’s sisters, and the sum total of Belles of their generation, as far as they know. Camellia desperately wants to be the favourite, to be the best (Why she wants this is not entirely clear to me. The position seems not to come with any real perks, apart from status, and will only last for a relatively brief period of time. But I’m not an adolescent.) and she breaks the rules in her test in order to impress. When she’s not chosen, she’s gutted. Her new role at a teahouse leaves her feeling as though she’s drowning in work, and she finds there are secrets that have been kept from her. When the chosen favourite is disgraced, Camellia is called to court to take her place. At court, she learns that the queen’s elder daughter (and heir) is unconscious with a mysterious illness, as she has been for some time, while the younger daughter, a girl about Camellia’s age, is revealed to be a dangerous sort of Mean Girl: paranoid about her beauty, determined that no one should be more beautiful than she is (or more powerful), erratic, and inclined to treat other people as disposable props in her life. Other members of the royal family are similarly self-involved: Camellia faces a rape attempt by a prince of the blood, for example.

Camellia finds herself with few allies, and those doubtful. (One of them is the soldier assigned as her bodyguard, a man with a good relationships with his sisters who seems to fall easily in a sibling-like relationship with her.) She finds herself faced with secrets and lies and a court determined to use her—and discard her when necessary.

Ultimately, The Belles didn’t work for me. It will work for other readers: readers less jaded by reading so many stories of young people discovering that there are Terrible Truths in the world, and readers less alienated (as I discovered I was while reading The Belles) by a rhetoric which emphasises beauty—in form and culture—without drawing attention to the hypocrisy of extolling beauty of form in a society that seems to thrive on ugly behaviour. Clayton perhaps intended to point to this contrast, but it doesn’t come across very strongly.

As for those Terrible Truths… there’s a whole lot about the Belles that strikes me as either implausible from a character point of view, or illogical from a social/worldbuilding point of view—including Camellia and her sisters’ ignorance about the “secret Belles” and their apparent lack of curiosity about the underpinnings of the Belle system, and the fact that their “mothers” appear to have told them very little about the outside world. Structurally, too, the pacing—especially as regards the revelation of each new secret—feels a little uneven. The Belles ends without resolution, holding out the prospect of sequels to tell us what becomes of Camellia and her emotional journey.

That said, Camellia is an interesting character, and Clayton gives her a compelling voice. This is a promising first (solo) book, one full of many striking ideas, from a talented new writer. I look forward to seeing Clayton polish her work in the years to come.

The Belles is available in the US from Freeform Books and in the UK with Gollancz.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.